The vaginal microbiome: what you may not know about it

We often hear about how important is to have a healthy and balanced gut microbiome. We hear that gut bacteria are very much connected to us: from directing our food cravings to allergies, inflammation, diabetes, and even cancer.

How much do you know about the vaginal microbiome? Are these bacteria the same? Do they produce similar effects on the vagina as in the gut? What about cancer?

Vaginal vs Gut microbiome

One of the biggest differences between the gut and vaginal microbiome is the number of different bacterial species that are part of the microbiota. When we think of a healthy gut, we usually think of very high bacterial diversity. The more, the better. This is because a complex microbiome can utilize all types of fiber found in plant foods and provide us with a variety of beneficial compounds.

However, the vaginal microbiome is quite the opposite. A healthy vagina is comprised of mostly Latobacillus spp. (70-90% of the total bacterial species). Most women will have one of the 4 dominant species: L. crispatus, L. gasseri, L. jensenii, or L. iners. But not all are created equal. Research is showing that L. crispatus is the most protective and beneficial for us, while L. iners is a bit more inflammatory and may lead to negative outcomes down the line.

Bacterial Vaginosis = Altered vaginal microbiome

An unhealthy vaginal microbiome is called bacterial vaginosis. This term refers to a reduction in Lactobacillus species and an increase in anaerobic bacteria (Gardnerella vaginalis, Prevotella spp., Mobilincus, Atopobium vaginae) and many more.

It is not yet very clear why this microbiome change occurs and where do the bacteria come from. One hypothesis is that these bacteria are already present in the normal vaginal in very small amounts. The other possibility is that these bacteria are passed during sexual intercourse. This is thought to be the case because the risk for bacterial vaginosis is increased in women that have multiple sexual partners and do not use protection during intercourse.

Other factors that may contribute to bacterial vaginosis include hormonal changes, menstruation, pregnancy, antibiotic therapy, hygiene, and even the socioeconomic status of the woman.

Do you have an altered vaginal microbiome?

Not very reassuring, but most infections are asymptomatic!

However, if you do have symptoms, you may notice vaginal discomfort, a non-itchy fishy or malodorous creamy discharge, and redness.

If you have the possibility, the best would be to test which bacteria are part of your vaginal microbiome. This way you get direct confirmation of the health state of your vagina. Unfortunately, this is not routinely done by the doctor.

Should you care about your vaginal microbiome?

Since most women do not have apparent symptoms, it is tempting to think that there won’t be negative health consequences. Quite far from the truth!

There are plenty of studies linking bacterial vaginosis with problems during pregnancy and delivery, such as miscarriages, low birth weight, preterm birth, or postpartum infections. Bacterial vaginosis can even interfere with in vitro fertilization techniques and reduce its efficacy.

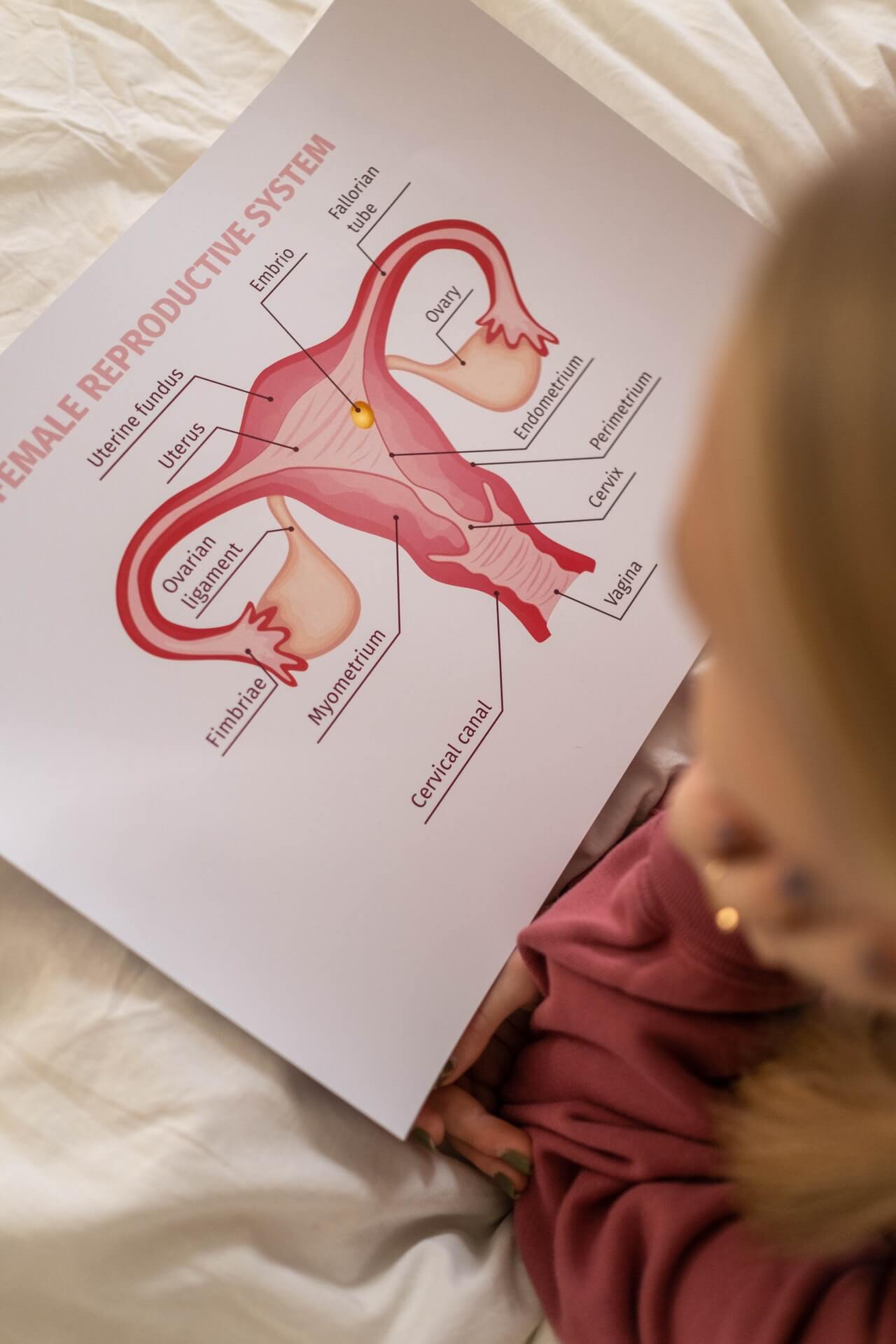

Moreover, having an unhealthy vaginal microbiome, even without symptoms, can increase the risk for sexually transmitted diseases like HIV and human papillomavirus (HPV).3, 4 This is not good news, since HPV infection is the major cause of cervical cancer! Therefore, having an imbalanced vaginal microbiota is linked to cancer development.5, 6

What can you do to reduce the risk of Vaginal Dysbiosis?

Since these pathogenic bacteria seem to spread between couples, it is wise to use protection during intercourse and stick to one sexual partner whenever possible (and desired!).

Moreover, any practice that alters the normal pH of the vagina (pH ~4) is disadvantageous. For instance, some women practice “vaginal douching” in an attempt to “clean” the inside of the vagina. This will change the vaginal pH, creating a more favorable environment for anaerobic bacterial overgrowth.

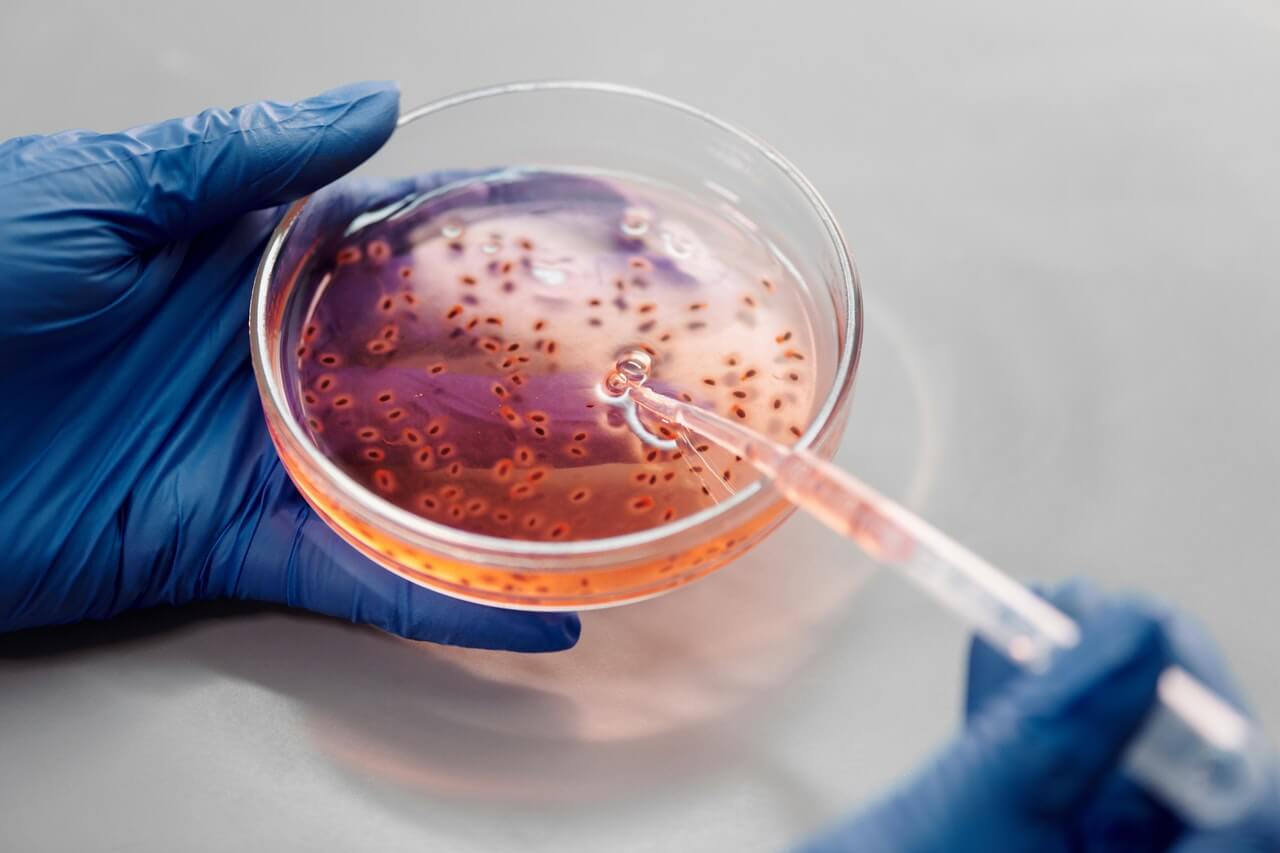

Lastly, vaginal-administered probiotics may be useful to prevent or treat bacterial vaginosis. A probiotic mixture including Lactobacillus plantarum and delbrueckii has shown promising results in vitro.7 Oral probiotics may survive the intestine and arrive at the vagina because of their proximity to the rectum. However, more studies are needed in this area.8

What are the open questions for research?

We want to answer the following:

- How do these anaerobic bacteria compete with beneficial Lactobacillus spp.

- How do they affect the risk for STIs and cause negative outcomes during pregnancy?

- How can we reduce and eliminate these bacteria?

There is a lot of information on some of the pathogenic bacteria (Gardnerella vaginalis, Prevotella bivia, and Atopobium vaginae). However, more bacteria come into play, such as Prevotella timonensis. And this is my favorite! Our research focuses on this bacterium and tries to understand what is its role in such a complex microbiome. One of the reasons that make Prevotella timonensis very interesting to us is that by having this one bacterium, women are at higher risk for HIV-1 infection!

Pathogenic bacteria affect vaginal epithelial cells and immune cells in multiple ways

- Bacteria degrade the mucus layer that covers epithelial cells to a very high extent. They can use enzymes to break down the mucin structures and reveal the surface of the epithelial cells.

- These enzymes can also reduce the effectiveness of antibodies (IgA) that are secreted by our immune cells within the vagina.

- Bacteria secrete short-chain fatty acids and other compounds that increase the pH (more basic), making it harder for Lactobacillus spp. to flourish.

- These bacteria also produce substances/metabolites that inhibit immune system activation, therefore immune cells are not fully active and can’t defend the vaginal tissue.

- Different bacteria collaborate to create complex biofilms, which are super resistant to many antibiotics (including those we currently use to treat this disease). This leads to high rates of relapse and recurrence.

My view

It is fascinating to realize how much microbiomes from several parts of the body differ. Even the concept of what a “healthy” and “diseased” microbiome should look like, varies depending on body location.

I am very enthusiastic about this line of research! Any piece of information we can provide will be used to find a better treatment for bacterial vaginosis.